Since I bought this domain, I’ve wanted to consistently post on a monthly basis. Obviously, that hasn’t happened.

While some of that is attributed to things like life changes outside of my mental health and my lack of a good attention span, a lot of it has been due to having no emotional motivation.

I posted a lot during the winter – this was due to a “low-low” in my depression (I plan on making a post in the future discussing my mood disorder). Although the fluctuation of my depression made it challenging to do simple, everyday tasks (like eating), I used a lot of the emotions I was feeling in writing. I’ve done this since I was a child, by putting my own feelings and struggles into characters in my writing.

While I’m still working on my first full-length fiction novel, I haven’t done anything on this blog, or even finished writing I originally intended to post.

Partly because I’m doing better – well, better than in the winter. Like everyone, I’m still facing challenges, some that are too difficult to deal with right now; I actually made the choice to leave therapy. (In my adult life, I’ve never been too keen on sticking to therapy for long periods of time.) For the first time, I’m seriously planning out what I want to do with my life, and part of that is going back to school. I want to see myself happy and successful on my own.

I wish there were something I could recommend to feel more hopeful or “get out” of a dip in depression, but there really isn’t anything. For people with mood disorders, both external and internal factors contribute to instability. I’ve had a lot of medication changes – none of which have caused more optimism or level-headed thinking. I suppose the biggest thing is that I’ve been attempting to put myself first, rather than the unhealthy habits I was following before.

I have more writing I’d like to post soon, and I also deeply appreciate it when people send suggestions. Thanks for reading. x

Know your rights: speaking up

I was submerged in the psychiatric world at such a young age that it’s foggy to remember every doctor and therapist. As a child, my parents sat in on many appointments and usually did most of the talking.

As I got older and began seeing psychiatrists on my own, I felt afraid to speak up—I wanted to trust them. Medication is scary and often dangerous. I didn’t want to read the side effects or risks; it was easier to have them write a prescription and send me on my way.

I didn’t start speaking up about my own well-being to psychiatrists until I was around 16. Unhappy with my medication, I talked to my psychiatrist at the time, who casually mentioned that diabetes-like symptoms—such as blood sugar issues—were common with this medication and something I was at risk for.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I remember asking, shocked.

“I didn’t realize you wanted to know,” he responded carelessly.

While I’ve disliked many of my past doctors (in general—not just those in mental healthcare), I do wish I’d had the courage to say something before that incident. Over the years, my trust in doctors has plummeted, leaving me skeptical whenever I need to see a new one. Unfortunately, I often end up being right to feel that way.

The silver lining is that I’m very forthright now. I’ve had the same psychiatrist for the past few years—someone I highly respect—but I now have clear requirements, boundaries, and expectations for any doctors or therapists I encounter, both now and in the future.

I’ve been disrespected in ways I can’t fully articulate. Sadly, the psychiatric world is typically a space where psychiatrists, therapists, and psychologists can get away with almost anything at the patient’s expense.

I know how difficult it can be to step out of that hard-to-describe, odd comfort zone of staying silent and to stop letting your doctor act like a lazy pill-pusher. It’s challenging and uncomfortable to navigate. That’s why I wanted to share a few of my standards, as well as what I typically say in a consultation.

Here’s a summarized version of what I’d express to a new psychiatrist during an initial consultation (along with the implied standards and boundaries I carry into any patient/doctor relationship):

“I’ve been taking medication for most of my life and have been on dozens. I like to do my own research before starting a new one or increasing a dose. If I’m not comfortable with the risks or side effects, I won’t take it—unless it’s absolutely necessary, which is typically in very rare circumstances. I will not allow a doctor to talk down to me or disrespect me in any way. I want a psychiatrist who is knowledgeable, treats me like a human being (not a lab rat or an experiment), and is completely honest. If at any point I feel that my psychiatrist or therapist isn’t meeting my standards, I have no problem walking out of an appointment—I’ve done it before.”

To save time, I usually bring my own paperwork in addition to filling out the forms they provide (which, frankly, they should already have on hand). This includes a list of medications with dosages and dates, past doctors, other health issues, and any important or impactful life events. My current psychiatrist keeps my medication list on file, and it’s helped us both avoid playing an unpleasant game of psychiatric drug Russian roulette.

Reading this, you might be thinking, “You kind of sound like an asshole.” Honestly, you’re not wrong! But it really comes down to the tone you set. If I’ve chosen a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other provider based on good reviews, I want to come in with a tone that’s firm enough to show I’m serious, but also respectful enough to convey that I’m there because I need their help.

If the provider is a good, insightful doctor, they’ll completely acknowledge your point of view, and you’ll build a mutual understanding based on respect.

Starting the process of standing up for yourself can be intimidating, but it will benefit you in the long run. You are your own person, and you deserve to be treated like one—not like a lab rat.

Adjusting: hospital to home

2024 was one of the hardest years of my life for countless reasons — I was not myself. I fell into a place no one wants to be, which landed me in the ICU for almost a week. When I finally got home, everything felt strange and unfamiliar, and adapting back to reality seemed impossible.

My body was incredibly weak — I had barely eaten anything, was severely dehydrated, off all my medications, and extremely sleep-deprived. I had trouble getting up and down the stairs and in and out of bed — everything hurt. My mind and body were exhausted.

There were so many aspects to healing: I was still going through withdrawal after abruptly being taken off all medication, processing everything I had just been through, trying to regain physical strength, and dealing with the psychological effects of being unmedicated. (While I don’t feel comfortable talking about what that feels like for me, I will say that I am not a threat to myself or others.) I was seeing doctors, trying new medications — I felt so vulnerable and overwhelmed.

I’m incredibly lucky to have a lot of support — I recognize not everyone does. Still, it was a very lonely and confusing time in my life. I didn’t think it would be possible to return to a “normal” life — and more importantly, to a life that was an improvement from before. But with the encouragement of my family, I was able to make small steps every day, like leaving the house (even if it was just for a drive or to pick up a prescription), improving my diet, and seeing doctors who knew how to help me.

I tried to do everything I could to help myself. I’m extremely self-aware of my emotions and how my body is feeling. I tried to accept that this was a time when I needed to focus on getting better. Being in that mindset can be difficult — I was so angry that I couldn’t do the simple things I used to, like folding laundry or taking my dog for a walk. But the idea that you have to get better immediately and feel fine won’t ease any of the stress. It’s challenging, but approaching everything slowly and with patience is healthier for both your mind and body.

That was almost exactly a year ago. Eventually, I hope I can talk more in-depth about what I went through and what led up to it. I think it’s important for others to hear. Unfortunately, it’s something that’s far too common, many people experience it. My life was never the same afterward — in both good and negative ways.

I’ve been doing quite a bit of reflecting. Just a year ago feels like a lifetime ago. The adjustment after coming back from the hospital can be hard and scary — but it does get easier.

Skin and psychiatric medications

When I was a child, I was naturally very tan—not just during the warmer months either. Year-round, my skin was an olive gold, becoming even darker in the summer. I also tanned extremely fast. During the summer, my siblings and I had an above-ground pool we’d spend hours in, and after just 10 minutes, we’d compare tan lines.

I’ve talked before about how I started medication at a very early age, but I didn’t start to see changes in my skin until I was about 13.

It seemed like it happened overnight: I went from my normal skin color to a blue—gray and sickly pale. It wasn’t even like I had a “pale” skin tone—I was just simply colorless.

I didn’t know until recently that even my father noticed. He recalled how my skin had become gray and ashy, losing all color. I hadn’t realized how noticeable it was to those around me.

Frustrated that I could no longer tan, I started spray tanning regularly when I was 14 (and I still do). Often, I feel like I don’t recognize the pale, bluish reflection in the mirror when I don’t have a fake tan. But I thought—this can’t just be me, right?

I’m part of various groups that discuss psychiatric medications, and multiple times I’ve asked fellow members (who have been on long-term prescriptions) if they’ve noticed any changes in their skin. I wasn’t shocked—but a bit relieved—to find out that I wasn’t alone. The posts were filled with comments—some just a “yes,” others more detailed. One person mentioned how their veins had become more visible over the years as their skin lost color. Another said they had also lost the ability to tan. Many were surprised but felt reassured knowing they weren’t the only ones experiencing this.

I haven’t found much information online about psychiatric medication causing an overall loss of skin color (particularly with long-term use), but there is plenty of evidence that psychiatric drugs can affect the skin.

Many cause sun sensitivity or photosensitivity—I started to notice this about seven years ago, when I got a sunburn for the first time even while using sunscreen. After that, it only got worse. Just sitting in the car on a sunny day would irritate my skin.

Hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation can also be caused by specific medications, along with other skin conditions, such as marks or discoloration.

Unrelated to skin color—but still relevant—is the increased risk of acne on certain medications.

I’m still hoping to find out more about why this happened to me and others. When I’ve talked to my doctors—especially those in mental health—they haven’t had any answers. Because so much hasn’t been studied long-term or thoroughly enough in the psychiatric field, there just aren’t many answers. Many side effects and long-term effects are still only assumed.

I’ll conclude this post by saying this: don’t let this scare you. One side effect—even if common—is not a guarantee that it will happen to everyone. And if this has happened to you, I’d be interested in talking.

Not having my natural skin tone has affected my mental health deeply, and I know it has for others as well.

Lithium

A few posts ago, I wrote about starting a new medication—one that felt more “extreme” than others I’ve been on.

I’ve been taking Lithium since the end of March, and it’s already been an interesting journey. But let me backtrack to how I ended up being prescribed it in the first place.

2024 was incredibly difficult for me for a multitude of personal reasons. Looking back, it probably would have been helpful if I had started taking Lithium in the fall of that year, as I had begun noticing some concerning symptoms.

Although I prefer to keep my diagnoses and ongoing work with my doctors private, I decided to go on Lithium after experiencing an emotional “high” followed by a deep crash—a severe depressive episode.

I remember sobbing in my room, feeling hopeless and broken. Fortunately, I have the option to text one of my doctors, which I did. I updated him on how I was feeling and explained that I needed more support. The medication I was taking at the time just wasn’t enough. (While I know medication isn’t a complete solution, depending on one’s symptoms, they may need a stronger dose, additional medication, or a different one altogether.)

He gave me a list of medications that might be helpful for what I was experiencing. I read through all the side effects, effectiveness rates, and risks.

None of them felt like a good fit—each had negative aspects I wasn’t comfortable with, and some posed the risk of worsening issues I was already dealing with. When I explained this to my doctor, he recommended Lithium.

I was very afraid to start it. I knew about the risks, especially Lithium toxicity, which can cause seizures, coma, and even death.

But I also knew I needed something stronger—I couldn’t keep living the way I had been. I was hurting myself and the people around me.

I started on a very low dose, though Lithium dosing is typically monitored through blood levels—so a “low” dose for one person might be a “normal” dose for another.

The side effects weren’t awful and seemed fairly typical. I joined multiple online support groups and forums (which have been incredibly helpful), and other people shared that they experienced similar symptoms.

For me, the most noticeable side effects were headaches, fatigue, and stomach issues. I also lost some weight—not a common side effect, but not an unheard-of one either.

Since then, my dose has been increased. It’s been a learning process, and I’ve had to make some lifestyle adjustments. I can’t have caffeine or alcohol anymore (though I rarely drank anyway), and I have to be mindful of my water and salt intake. I also try to avoid getting overheated and make sure to take my medication at the same time every day. Being consistent and aware helps reduce the risk of Lithium toxicity.

Because Lithium can affect the kidneys and thyroid, I now need regular blood tests and ongoing monitoring of both.

Overall, the experience has been positive. I can think more clearly, my depressive episodes aren’t as intense or long-lasting, and I don’t feel as self-destructive. The harmful behaviors I was struggling with have lessened. I also have more clarity when dealing with stress, something I really didn’t have before.

It hasn’t “fixed” everything—I still have a lot of work to do with my therapists and doctors—but I feel hopeful, and I’m proud of myself for taking the initiative.

Printable mood chart and notes

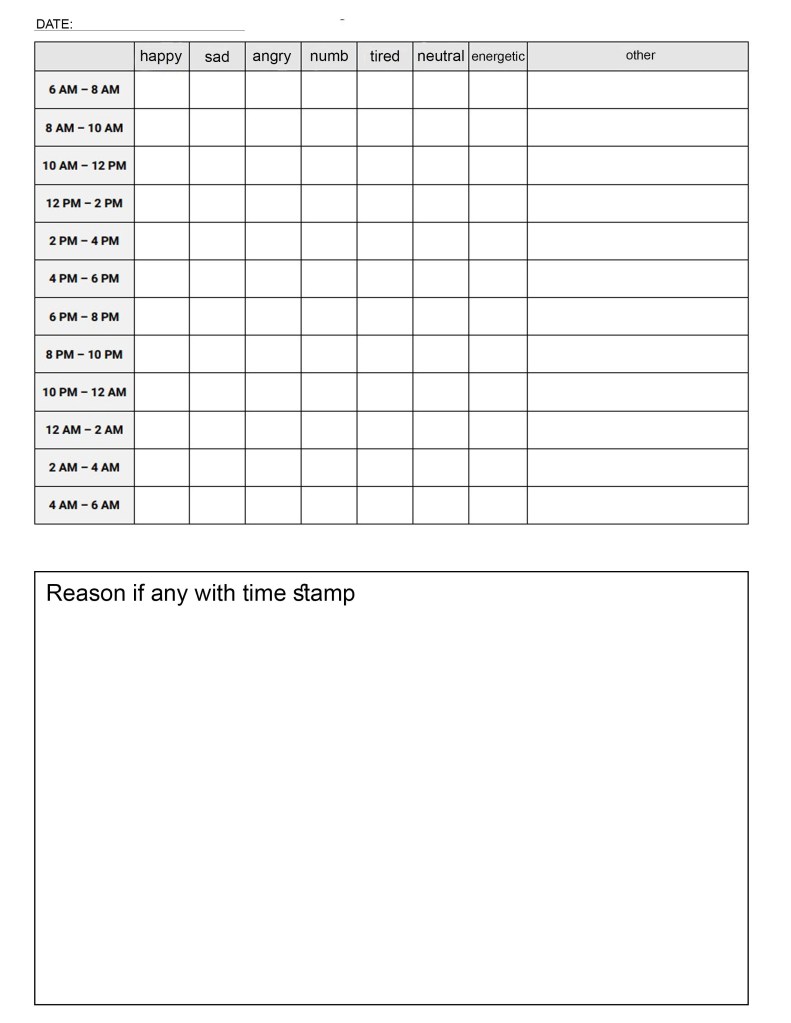

Recently (at the request of one of my doctors), I’ve been keeping track of my mood. A lot of daily mood trackers are available online; however, they usually only give the option to rate the day as a whole. Using my mediocre Photoshop skills, I modified an hourly one with emotions I typically experience, along with a blank space for any others.

I also created two notes pages—one to explain any specific reasons behind mood changes, and another to keep track of any physical changes (e.g., side effects from medications or health issues that might correlate with mental health). I also included sections for sleep and eating habits, since these can strongly impact mental health.

Not sure why the font looks a little weird, but hopefully this is helpful to anyone who needs it.

Teenagers, young adults, and medication

As I mentioned in my last post, I truly believe medication should usually be a last resort—not just because of the risks and side effects, but also because other forms of treatment can often be more beneficial.

However, over the past ten years, I’ve seen a significant increase in both teenagers and young adults taking psychiatric medications as a first option. Really, this is none of my business. I’m not a psychiatrist (nor have I ever claimed to be), and while I don’t know (or want to know) every single personal detail of these individuals’ psychiatric situations, I do care about the effects—both now and in the long run.

Taking psychiatric drugs isn’t funny, cool, or something to make “relatable.” These medications have a disturbing history that has ruined the lives of innocent people. There’s also little (and sometimes no) information on their long-term effects, especially in prepubescent children and teenagers.

But I’m continuing to see young people joke about being on these medications. While I understand the desire to make light of a stressful situation, the way it’s being done is not only inappropriate but also harmful. I’m really sick and tired of seeing young adults think it’s “cool” to drink alcohol while on medication, brag about mixing recreational drugs with it, or act like it’s no big deal to start taking psychiatric drugs—as if it’s actually a “fun” thing to do.

The longer you’re on medication, the less effective it may become. The side effects can be brutal. Some medications, if not taken seriously, can put you into a coma. You can develop serotonin syndrome from the wrong prescription or from taking medication you don’t need at all. Some can even cause symptoms of psychosis. These are extremely dangerous and serious issues that we should not be treating casually.

My entire life, I’ve wanted people to treat mental illness like physical illness—to offer the same sympathy and support, and to recognize improvements. But with this kind of attitude, people are only creating bigger problems for the future and influencing others to make harmful decisions. I’m not against medication, and I don’t think people who need it should stop taking it. But to say I’m disappointed with what I’m seeing would be an understatement.

My experience with psychiatric medication: risks, side effects, and more

I don’t remember the exact age I started taking psychiatric medication, though I’m almost positive it was at age 9. I started with one, and then the doctor I was seeing at the time added two more. I didn’t have many side effects; I basically just felt very tired and slept a lot. I do remember walking outside with my friends and thinking, “life is beautiful.”

The history of mental illness medication is long and confusing. People have been over-prescribed, prescribed when they don’t need it, and given the wrong type of medication for decades. Unfortunately, this is still the case.

There’s an odd imbalance now, with people who are on medication but don’t need it, and people who need medication but aren’t on it—mostly due to the unfortunate, strange circumstances of how mental health is viewed in society. (I could go on about this.)

Psychiatric medication is not something to joke about or take lightly. The progress made inside the psychiatric world is incredibly slow in basically all aspects, but especially medication and alternative treatments. Of course, ultimately it’s up to the individual and their doctor to decide if that person should go on medication, but in my opinion, it should be a last resort.

I’ve been on dozens of medications, and this has given me the opportunity to learn about different categories of medications, risks, side effects, and more. If I went through every medication and the side effects I had, it would be extremely boring, so instead, I’ll just tell you about some of the side effects I experienced.

A few years ago, I wrote about my Paxil experience (that post is still up if you’re interested in reading it), as it was the most challenging medicine to both start and stop. Throughout the years, from the medications I’ve been on, some side effects I dealt with were: stomachaches, headaches, fatigue, excessive sleeping, exhaustion, loss of appetite, dizziness, “brain fog,” nightmares, tremors, heat/cold sensitivity, sweating, dehydration, dry mouth, taste sensitivity, “zoning out,” short-term memory loss, body aches, heightened stress, and motion sickness.

These, unfortunately, are all very common. A side effect can also happen at any point and can be anything. Often, they go away after a few weeks, but handling them can be extremely challenging.

There were two occasions I can think of specifically when I was very concerned: once when I was 13, I had a migraine that would not go away, and half of my face slightly swelled. I ended up going to the emergency room, but they didn’t really know what to do. Another time, when I was 22, after about two weeks on a medication, while I was experiencing memory loss and stomach aches, I completely blacked out. I was ready to go to sleep for the night but instead woke up my parents because I felt so ill. I don’t remember anything that happened, but I was awake the whole night and sick. I called my doctor in the morning, who advised me to stop taking it immediately.

Oftentimes, people will fall victim to “a medication for a medication.” Usually, from psychiatrists who are pill pushers rather than doctors, when a medication causes a side effect, they’ll prescribe another to counteract that. (Cue “Doctor Blind” by Emily Haines). When I was nervous to speak up for myself, this happened to me, and I can see how easy it is for it to happen to others who are simply looking for answers.

If you need medication, do what’s right for you. But from my personal experience, it’s really beneficial to try other things first. Psychiatric medications can be terrifying for a multitude of reasons. I wish more people would acknowledge this and also be more understanding of those who need them and have to deal with the physical and emotional stress surrounding them.

Changes: a small update

Recently, I’ve experienced some significant life changes. Since childhood, I’ve received multiple diagnoses but never a single “blanket” diagnosis (which isn’t uncommon and there’s nothing inherently wrong with it). However, after a few months of emotional spirals, I decided to return to therapy and also discuss new medication options with my psychiatrist.

I’ve seen dozens of mental health professionals over the last 21 years, and fortunately, I currently have an excellent psychiatrist who suggested a medication that is considered much more intense—and even risky—than the majority of medications I’ve been on before. (While I don’t feel comfortable sharing which one it is at the moment, I hope to do so in the future.) I agreed and immediately began the process, as I needed tests done to start the medication. I also had to make dietary changes and will need to be more conscious of how I’m feeling physically.

My therapist is helping me determine whether there is, in fact, a single “blanket”diagnosis—which is highly likely. However, to be both ethical and accurate, a formal diagnosis can take weeks or even months, especially for what we are considering.

At first, all of this made me feel, well, weak. I know I have a lot of things “wrong” with me—mental illness has essentially always been a part of my life. But going through big changes like these can bring up new feelings, some difficult to describe, and others that make me feel vulnerable and small.

I’ve been trying to manage a range of emotions: anger, confusion, sadness, and anxiety. There are times when I feel inferior because of my mental health. I’ll compare myself to others and think, “Why can’t I be pretty?” or “Why can’t I be successful and independent?” While my insecurities about my appearance are something I try not to dwell on, I do remind myself of what I actually define as success.

When I’m feeling bad about myself, it’s easy to think I’m not accomplished because of what I’m dealing with. But I remember my core beliefs—that I’ve never been someone impressed by others’ jobs, wealth, or material possessions—and that I don’t need or want those things to impress myself. I value success based on people’s characteristics, such as emotional intelligence, humor, and empathy—all of which I believe I possess. It can be hard when you’re already feeling overwhelmed and see others who appear happier based on what they have. But remembering what you actually value can help bring you back to yourself.

I’ve been struggling with remembering that I am not my illnesses; I am still me, and I am so much more than the problems I face. I also balance that with the fact that I still need to work on managing my symptoms; they are not excuses, nor are they always justified for my behavior. However, acknowledging that I’ve been wrong while dealing with these issues—and trying to apologize to both the people I’ve hurt and myself—is important. I’ve been trying to remind myself to act as though everything were a physical illness, and treat myself the way I would if I were dealing with that. We can be so hard on ourselves when it comes to mental illness.

Both my body and mind have been so exhausted, but I’m trying to make positive changes in my life. I’m hopeful that this medication will take effect soon, and that I’ll gain some clarity with a new diagnosis and treatment. While I wait, I’m working on making peace in my personal life through apology, being more understanding, and planning for a better future.

Reflection: trauma connections

Sometimes, two people who have experienced trauma will bond for many reasons. Often, they talk and relate to one another, or they both recognize a familiarity in each other. However, this can lead to further problems.

I’ve had the unfortunate experience of trying to convince people from my past to get help—both friends and romantic partners. From extreme abuse to an absent parent, I’ve realized that when someone opens up, it’s clear they won’t be able to move forward without therapy.

Due to my extensive history in the psychiatric world, I understand the dislike for it. I’ve had my fair share of evil (yes, evil) psychiatrists, incompetent therapists, and lazy doctors. There is still a stigma surrounding seeking help, especially for men, even though it is more accepted than it used to be. At the same time, I’ve also seen the improvement people can make through talk and behavioral therapy. Not everyone needs medication.

So, what could be the outcome of a “trauma bond”? Of course, I can only speak from my own experience. When I’ve been in situations where I’m involved with someone who has unresolved trauma, I usually get frustrated. That person often experiences a chain reaction of events—one thing after another—that leads back to the root cause, which can help explain their behavior. I’ve found that even suggesting therapy or treatment makes them defensive; they often feel they’re “too good” for it or have convinced themselves they don’t need it.

In romantic situations, I’ve noticed that many men tend to project their negative emotions onto me, sometimes becoming both verbally and emotionally abusive. Others will detach themselves or “ghost” me, then move on to another woman, repeating the same behavior. These are all forms of unhealthy coping mechanisms, but they serve the purpose of protecting the hurt parts of themselves. Of course, this is not an excuse for any kind of malicious behavior—it’s just an explanation.

Connecting with these types of people can feel like trying to force two negative ends of a magnet to connect. I have my own fair share of trauma, and I am in no way completely “healed” or perfect. I’m extremely aware of when I’m in the wrong and how I need to improve. But this is something I talk about and work through in therapy and psychiatry.

Many people who have experienced some form of trauma connect easily with others who have the same, as there’s a sense of comfort and understanding. There are also more bleak reasons, such as someone recognizing that another person is emotionally vulnerable due to trauma and seeing them as an easy target to manipulate. This can inflate the manipulator’s ego (egotism can be a sign of unresolved trauma).

The bond between two people with trauma is extremely complex, and it’s a circumstance I’ve found myself in too many times. While everyone has problems, challenges, and hardships, not everyone has experienced the same level of trauma. For me, it’s a unique experience because I’ve been receiving help for most of my life, even though I didn’t ask for it and wasn’t old enough to recognize I needed it. So, when I find myself in these situations, there’s an odd imbalance.

However, I’ve had positive experiences as well. There have been people who were in intensive therapy and able to give me insight into what they had learned, or others with whom I could relate. Sometimes, our struggles can bring us together in the best ways. But always make sure you’re doing what’s best for you. As much as I wish people who need help would accept it, you can’t force them—you can only hope that one day, they’ll come to that realization.